Kepler Q1-12 Release Frequently Asked Questions

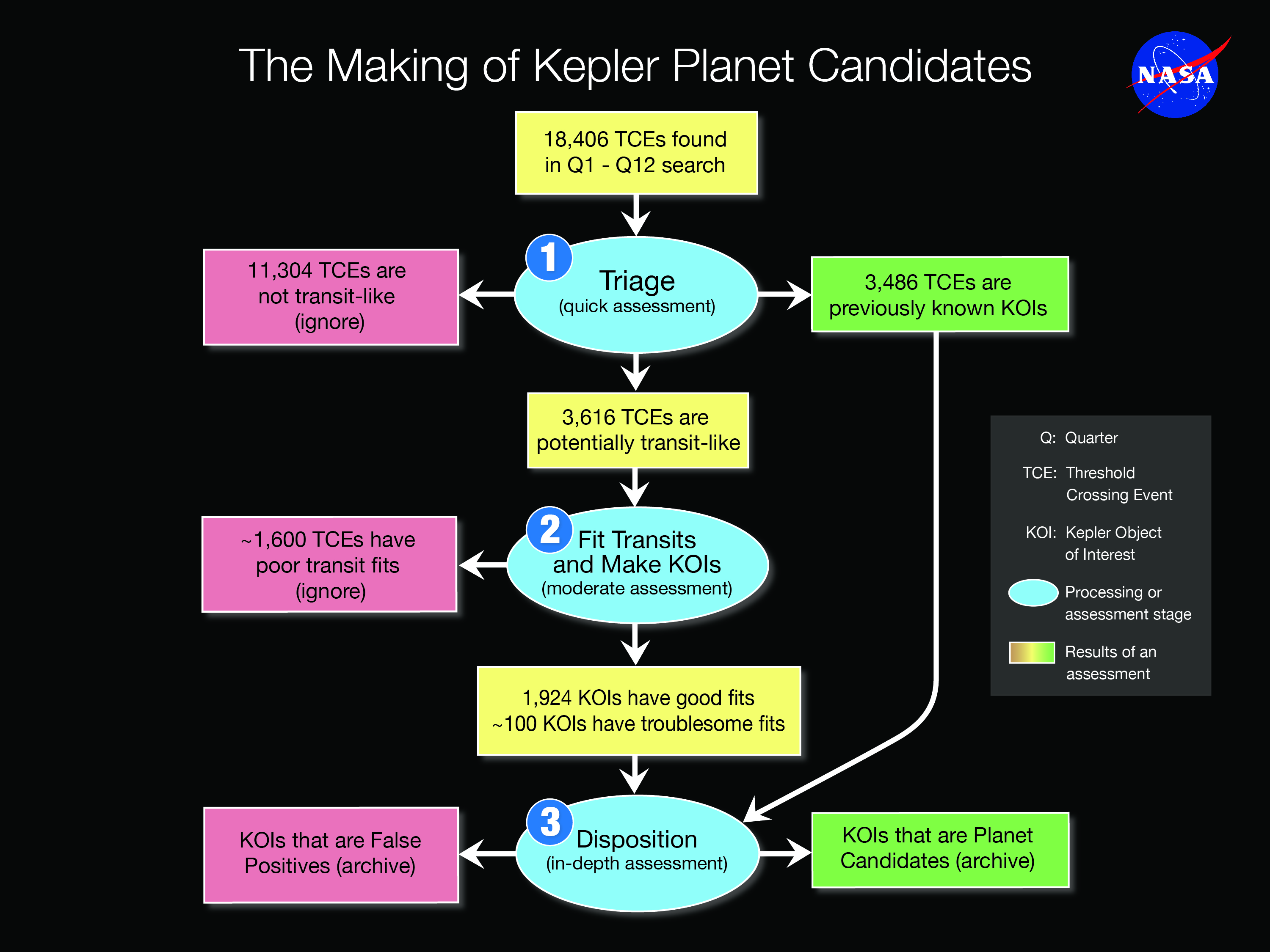

Figure 1: The three stages of vetting Kepler Transit Threshold-Crossing Events (TCEs) for Planet Candidates. (Click image to enlarge.)

Q: When the Kepler mission delivers a new KOI to the Exoplanet Archive, does this mean the Kepler mission is delivering a new planet candidate?

A: No. When KOIs are first delivered their nature has not been analyzed completely. The term KOI means exactly what the name implies – Kepler has declared these to be "objects of interest," not planetary candidates. By promoting these transit-like signatures to KOI status, the Kepler Project is saying is that their light curves contain interesting patterns of repetitive dips that might indicate the presence of a transiting planet. However, there are several other ways to produce similar looking transit-like patterns. For example, the dips could be due to stellar variability, excess detector noise, other transient events associated with the spacecraft, or a background star occulting a second background star (i.e., a background eclipsing binary). We use the term "false positive" to describe those KOIs that are explainable by means other than the planetary hypothesis. We know that with further analysis, many of these new KOIs will become false positives.

Q: If the Kepler Project hasn't finished the analysis of KOIs, why are they releasing this information now? It seems rather preliminary.

A: The analysis is indeed preliminary, but it also represents a significant body of work and contains valuable information for the scientific community. To summarize the process of identifying KOIs. the Kepler project started with the light curves of nearly 200,000 stars that were observed for some or all processed quarters. That's a lot of data to plow through. When the Project begins searching data they typically identify 10,000-20,000 threshold-crossing events (TCEs). These TCEs had to pass a series of tests, each with a threshold, that were designed to identify the events that look transit-like. This list of TCEs and their accompanying diagnostic reports (i.e., data validation reports and one-page summaries) are also released to the public in tables through the NASA Exoplanet Archive. The criteria required to pass this first set of tests are intentionally lenient. The Project prefers to include many non-transit-like events at this early stage of analysis, rather than miss small, Earth-size candidates in long orbits – the hardest candidates to find).

Q: What guidance is there for the scientific community about using data within activity tables that are still "open?"

A: The value of the different stages of product delivery greatly depends on your scientific objectives. If you are looking for interesting KOIs to study or for follow-up observations then providing results in a sequential fashion is a big help. If you are trying to understand the statistical population of small planets in the galaxy, this delivery isn't going to hand you what you need until the activity table is closed, published and the nature of the population, detection algorithms and vetting procedures are well understood.

Q: With previous Kepler data releases, the term "KOI" was synonymous with planet candidate. Can you explain what has changed?

A: This is a common misconception. Actually, the definition of KOI has not changed; but the Kepler Project's reporting philosophy has. In the past, the Kepler mission published lists of KOIs that were deemed to be planet candidates; and separately posted the KOIs that were declared false positives at MAST (Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes). This may have given some the mistaken impression that all KOIs are planet candidates, but this has never been the case. For example, four of the first ten KOIs identified using the first month of data are currently marked as false positives in the cumulative activity table at the NASA Exoplanet Archive. The reporting philosophy has been modified so that all KOIs can be archived in one place. This makes it much easier to change the status of a KOI from "planet candidate" to "false positive," and vice versa. In addition, the new format enables more rapid release of incremental information as progress is made.

Q: How are KOIs found within the list of TCEs?

A: The Kepler Project evaluates each TCE using objective criteria that are difficult to code into a computer algorithm. This exercise is called "triage" because it is a relatively quick assessment that eliminates the obvious false positives, while retaining anything that looks remotely transit-like for further assessment. During this exercise, most of the events produced by spacecraft transients and stellar variability are discarded. This is process step 1 in Figure 1 that summarizes the process using the Q1-12 TCEs and Q1-12 KOI activity table as examples.

Q: Is every TCE that passes triage automatically promoted to KOI status?

A: No. If at least two scientists determine that a TCE looks transit-like, then the light curve is fit with an analytic model of a transiting planet (Mandel and Agol 2002). If the model fit looks reasonable, then the TCE is promoted to KOI status. If the model fit is poor, then the TCE is ignored and receives no further analysis. As shown in Figure 1, slightly more than half of the TCEs that pass triage are typically promoted to KOI status. Moreover, many of the KOIs found among a TCE sample are old ones that were discovered and cataloged during previous transit searches. After triage, detailed attention is most typically spent focusing on new KOIs, found for the first time in the current sample. Many of the new KOIs will eventually become false positives, but the Kepler Project can afford the additional analysis because the number of light curves that require in-depth assessment has been reduced by a factor of 100.

Q: What does it mean to "disposition" a KOI?

A: Dispositioning is the final step of vetting KOIs. Dispositioning is the action of using a variety of analytical tests to label a KOI as a planet candidate or a false positive. The most common tests are documented within the one-page DV summary reports and full DV reports archived with the TCE tables. Dispositions are the current opinion of the Kepler Project regarding the nature of a KOI, although it must be noted that there are gray cases and users have freedom to disagree with the disposition using the statistics provided at the archive. Since there is a set of possible reasons for dispositioning a KOI as a false positive, there are future plans to flag false positives with an extra layer of detail that provides specific reasons for the decision made.

Q: Does the Kepler Project re-analyze old KOIs?

A: Yes. With more quarters of data and sequential improvements in diagnostic tools, some old KOIs will change status when the Kepler Project dispositions them again. (See process step 3 in Figure 1). Some planet candidates will become false positives and some false positives will become planet candidates.

Q: Will the Kepler Project redisposition all the old KOIs within each activity table at the archive as well as disposition the new KOIs?

A: That is the long-term plan. However, it is not possible to complete all this work before search results from the next run of the pipeline become available. Hence, the Kepler Project plans to disposition all of the new KOIs within each activity table, but a complete redisposition old KOIs is a future activity for longer baselines of data and even better diagnostic tools that are currently under development.

Q: In the Q1-12 data set, there are a surprising number of KOIs with orbital periods near one Earth-year. Do Earth-size planets tend to prefer Earth-like periods?

A: Remember that the Kepler spacecraft orbits the sun every 371 days. Given its extremely stable environment, some noise sources associated with the local detector electronics exhibit repetitive behavior with this periodicity. Since these electronics read-out the charge-coupled devices (CCDs), this noise is intertwined with the astronomical signals in such a way that the two are almost impossible to disentangle. Hence, this repetitive noise can mimic the signature of a transiting planet. Fortunately, we can identify these noise-produced TCEs and distinguish them from true planet candidates in one Earth-year orbits, but it requires a lot of effort. Although most of these bogus TCEs were ignored at the triage or model fitting stage, a small fraction of them have crept into the KOI population and still need to be identified and declared false positives. So, don't get too excited by the pile-up of KOIs with one Earth-year periods, or the smaller, associated pile-up at 180 days. Most of these are probably not real planet candidates; then again, there may be some real gems there. This explanation is documented more formally in the Q1-12 TCE Release Notes at the archive.

Q: Why weren't false-positive one Earth-year KOIs seen in earlier data releases?

A: The Kepler spacecraft is in a 371-day orbit (i.e., just over one Earth-year). Three transits are required to define a TCE (and therefore a KOI). Hence, the Kepler Project has just begun to see these bogus events now because the Project is searching three years (i.e., 12 quarters) of data for the first time.

Q: Are there other reasons for an increased fraction of false positives over time?

A: Yes. In the past the Kepler Project tossed out the eclipsing binaries (EBs) as soon as they were identified, so many of them have never been made into KOIs. This means that every time the Project search a data set for transits, they were finding and re-evaluating the EBs again. The decision was made from the Q1-Q12 activity onwards to pass EBs through triage, fit models to them, and turn them into KOIs. Now they are documented as false positives, providing a lasting record of past decisions that help to minimize the amount of work going forward.

Q: Are KOIs held back from the archive for any reason?

A: Yes, users of the archive will notice from time to time gaps in the sequential KOI numbers (i.e., some KOIs are missing). The missing KOIs are troublesome cases that require manual processing. For example, some KOIs are found but their properties calculated by the Kepler pipeline can be incorrect. For these KOIs, the Kepler Project need to recompute their properties before they can be delivered. By staging the deliveries as described, the best information is delivered to the community in a timely fashion rather than waiting for a complete analysis of all KOIs.

Q: Why are some columns in the TCE or KOI tables blank?

A: The propagation of information from the Kepler Project to the Exoplanet Archive remains a relatively new process. There remain wrinkles to iron out regarding some of the data. Empty fields will not remain so for long.

Q: What are the rules for displaying the precision of values and their errors in the TCE and KOI tables?

A: The number of significant digits for a property delivered to the archive by the Kepler Project is identical to the number of significant digits in the error. Large calculated uncertainties from, for example, a bad model fit, can cause less-than desired precision being reported for some archived values. Some values have too many significant figures because either the error bar was reported as zero, or the formal fit gave a very small error. The default behavior of the KOI table is to display +/-0 for values delivered as "NULL." This behavior is under consideration.